ARTICLE: Indie Film Budgeting Footnotes

Often-Forgotten Thoughts on Budgeting in the Independent Film Sector

:: by Josh Folan :: 5/12/19 ::

In the customary filmmaking development timeline, the first step one takes between a (relatively) finished script and producing it is to define the resources necessary to do so – also known as running a budget. What I’ve come to find in a decade-plus of producing at the low-budget/independent level is that there are two definitions of that word in that context; on one hand it is a line-by-line compiling of the cost of each and every item necessary to bring the script to screen as the director ideally sees fit, on the other (heavier) hand it is the amount of money you are able to access to bring the script to screen as the director ideally sees fit. It is very, very seldom these two definitions land on the same dollar amount in the independent filmmaking sector.

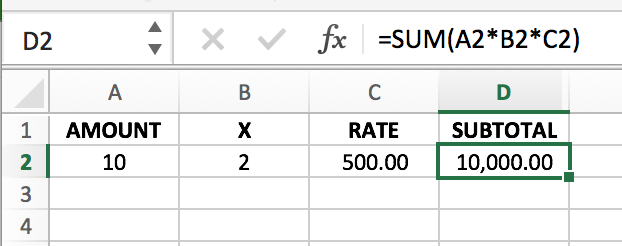

For that reason, I tend to approach budgeting from what I see to be the more practical of those two philosophies, the latter. Raising money is typically one of the more difficult parts of the filmmaking process, so I start by budgeting the film at the absolute lowest amount of money I can realistically foresee getting the script in the can at. The thing about this “you don’t say?” method is that the number one can deliver a film at is a highly subjective viewpoint, and heavily dependent on the experience and resourcefulness of the human being producing that film. A film can be distilled down to an elaborate sequence of multi-variable problem sets, and what a producer can and does plug into the variables in, and how they solve, those problems is ultimately how much the hard cost of making a film inflates to.

I’ve finished films at some bargain basement numbers — my first four produced features were delivered at $30k, $10k, $60k, & $35k – where we operated as leanly as we could because financing creatively risky films without name talent is quite a hard sell to both investors and distributors alike, even once you’re an experienced filmmaker…which I was not a decade ago. Point being, I have an understanding of where corners can be cut and where they cannot, and how to go about cutting them, in my independent filmmaking landscape problem solving. Here are some tips I’ve learned, often the hard way, in my travels.

Head Count

Every human being on your set has an exponential impact on the budget. There is the obvious cost of their labor fee, but you also have to feed, transport and simply have procured enough square footage for them to operate and exist in the little pop-up ecosystem that a producer must build in putting together each production.

There are further, less quantifiable, effects each additional person can also have on a production — inefficiency being one of them. It’s a tired adage to say time is money, but every second really does matter in low-budget scenarios and human beings are inherently inefficient organisms. They have to eat, sleep and appease a range of other self-serving wants and needs, which means they can be late. Or tired. Or unhappy. Or hungry. Or not paying attention. Or whatever. If three people have to communicate and be relied upon for a task to be accomplished, when it could be done by two people who are working a little harder, the low-budget producer needs to be able to identify that and hire stronger, and trusted, crew members that can handle that above par workload if they are capitalize on that cost-minimization opportunity.

The flip side of this is stretching a department’s personnel too thin, and losing time and quality because that department is overwhelmed and unable to deliver on a schedule that keeps up with the rest of the production. Being able to identify the areas of your crew budgeting where this minimalist approach is possible, and confidence in your ability to hire the kind of talent necessary to employ it at low-budget rates, is a producing superpower.

A real world example of this, in single camera production scenarios, is I’ve often hired a reliable assistant camera that I know can handle media management/DIT responsibilities as well. The indie filmmaking hustle tradeoff of that is there are plenty of cases where, after a fourteen hour day, I have agreed to stay late and finish, or handle altogether, the end of day media dump because that AC needed to go home right at wrap or they would have been exhausted the next day. If you need a lot of sleep to function well, independent film producing is probably not the line of work for you.

Craft Services

Crafty. In the grand scheme of planning a film production, budgeting for it included, the snacks and drinks lying around on a tired folding table in the corner can seem like a meaningless topic, but that couldn’t be further from the case.

As mentioned in the previous topic, inefficiency from your humans is a very real problem in getting your days on a low-budget shoot. The easiest way to breed that is to not keep them fed properly, both in the hot meals provided on meal breaks and the sustenance available to them in between those breaks. Artists tend to be more finicky in their dietary preferences than most demographics, and ensuring you accommodate those needs can go a long way in keeping morale up when the inherent difficulty of indie filmmaking rears its head. I always send out a google questionnaire to the full cast and crew right before production with a few simple but critical questions aimed towards ensuring three important states of being – dietary restrictions (full), allergies (alive), and what’s the one thing you most like to see on a crafty table (happy).

When it comes to budgeting for this, I find anything less than $5 per man/day is going to put you over budget on crafty if you’re actually making an effort to keep people anywhere near happy. That reality often manifests itself in going over budget on this line item, as no matter how strict you think you are able of being about your budgetary constraints, when you’re in the trenches it’s near impossible to tell a crew that’s busting their hump for you that you can’t afford simple food and beverage requests. A studio production is usually spending somewhere between $8-12 per man/day for below the line craft services, just to give that $5 figure some perspective. If you’re shooting somewhere well outside a major metropolis, you might be able to shave a dollar or two off of that figure, as things tend to be cheaper in small towns.

Post Minutia

Another often-overlooked budgetary area is post production. Independent projects frequently are light on post allocation to begin with, as the mentality can often be to just scrape together the resources to get the piece shot and worry about figuring out finishing funds once that seemingly-attractive problem set is upon you. I’m not one to deter this mentality if it’s necessary to get traction, as I do firmly believe raising money once you have a something to show besides a couple of pretty PDFs and/or a concept reel is far easier, but regardless of which route you arrive in post by way of, there are a few line items that come to mind for me as easily forgotten.

Captions: Even the barest of bones self-distribution plans will require these. Amazon, iTunes and most all other digital platforms require this as part of the delivery asset pool. Unless you’re doing it yourself – which, while possible, is an incredibly time consuming and laborious task – you will need to outsource this. The best deal I’ve found is Rev.com, they offer 99%+ accuracy for $1/minute.

Large File Transfer Service: Freelance post production in the independent film sector happens remotely by way of Vimeo and Dropbox, and I’m sure there are numerous other lesser-known comparables that run a little cheaper. The files will be large and the uploads frequent, so unless you’re fortunate enough to hire editors/vfxers/sound mixers/composers that have their own premium accounts on these platforms for you to milk bandwidth out of, you’ll have to foot the bill for it. The costs for this are constantly in flux, just go to the websites for the latest pricing options.

Film Festivals: Submitting to these things, particularly the good ones that will actually provide value to your film and career, is expensive. Those festivals can cost upwards of $100 for a feature submission on the latter deadline windows, so taking some time to sit down and map out your exact plan for festival submission – where, when, how many, how much – is an absolute must if you want to ensure you’re giving yourself a shot with those that can make all the hard work you put into a project actually have a chance of being seen by audiences.